Room 448B

Ethan Wood

For a brief, final moment, my sleeping body’s only companion is the dim, orange light filtering in through the tinted wall-length window from the parking lot four floors below. It faintly illuminates the pale blue walls: the one to my right fitted with a mounted TV—a black window to nowhere, and the wall in front of me, with two separate shelf-like protrusions, one of which holds the sparse amounts of zipper-less, string-less clothing I was allowed and a paperback copy of Calypso by David Sedaris. On the tile floor beside my bed, Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney rests—the cover curves slightly upward. From my peaceful corner on the left side of the room, I wasn’t able to see the large, wooden door, how it sits slightly ajar, or how it opens as three bodies enter—one of them you.

Your entrance is loud enough—this environment still new enough—to wake me despite the 25mg of trazodone I’d been given earlier that night in a tiny, white paper cup. Two orderlies escort you in along with a rolling blood pressure monitor. My brain barely registers your stray “Don’t wanna wake him,” before one of the orderlies gently touches my shoulder, says, “We’re just bringing in your roommate. Try to go back to sleep.” They sit you on the bed, or rather, the big, blue brick bolted to the floor fitted with a thin white mattress, thin white sheets, and not-the-worst white pillows.

Framed by the fluorescent lighting forcing itself through the doorway, yet shadowed by the orderlies, your blood pressure is taken, the cuff loudly inflating, crinkling as it tightens around your arm. After a full day here, I’ve become familiar with the sound. It’s part of my new routine.

Through slit eyes, I can tell by your dark silhouette that you’re a grown-ass man. Not ideal. As the orderlies tend to you, I roll over onto my stomach, putting pressure on the shallow cuts on my left hip. They don’t sting as much as they did yesterday.

Thanks to the trazodone, it doesn’t take long for me to fall back to sleep. Thanks to whatever pain it is you’re feeling, it doesn’t take long for you to wake me up again when the scrubs come back in to give you some Tylenol. I fall into some semblance of slumber, but a part of me wakes every time you stir on the other side of the room. You’re a stranger in this space that was solely mine for almost 24 hours. But it’s not just your anonymity, your involuntary intrusion, that’s keeping me alert. It’s your masculinity.

***

When Chance, the super tall orderly with glasses, wakes me up, the sun is brightly shining through the window-wall. I look across the room to where you’re lying. Only a tuft of dark hair is visible, peeking out of the lump of white sheets. Chance crouches down and hands me two paper cups—one pills, one water—as he tells me your name and asks me to notify anyone if I’m ever uncomfortable so they can make other arrangements. I nod, smile. Then he hands me a pen and paper and has me circle, between two options, what I want for breakfast, lunch, and dinner today.

After enjoying a splendid breakfast consisting of a soggy pancake, and an orange and apple juice that comes in what is essentially a pudding cup, I get my blood pressure taken and attend the first group therapy session of the day. Later, when I return to our room, hoping you’re still asleep. I push open the wooden door and step as silently as my grippy-socked feet can. I set a green folder containing papers full of exercises (identifying feelings, grounding, etc.) from group sessions on the floor beside my bed. I start to reach for the Rooney paperback but stop when I realize I need to pee. My only option is the toilet in our poor excuse for a bathroom—only a cheap, blue curtain separates it from the rest of the closet-sized space. This wouldn’t be a huge deal if it weren’t for the toilet’s ridiculously high-powered flush and the fact that I need you to stay asleep so I don’t have to interact with you. And yet: pee I must. I slip past the curtain—lamenting the lack of one for the shower—and piss as silently as I can, avoiding the water and hitting only the side of the bowl. Staring at the toilet, I debate whether to flush it, but instead do the next best thing and push the toilet’s handle down as slowly as I can, hoping against hope to reduce the sound. My ears are still met with a sonic expulsion of water. I hope to God you’re still unconscious.

I slip past the curtain again, and elect not to wash my hands because I’m not about to take another chance. The Rooney with its yellow cover lays on the white sheets. I’m about to grab it when you stir behind me, and the sound of your voice hits the base of my skull.

“Hey, sorry if I woke you up last night.”

My blood freezes. Not only do I now have to talk to you, I have to do so with the knowledge that you know I didn’t wash my hands after using the toilet. I grab the book and turn to see your face clearly for the first time. Your dark stubble has started to gray at your chin. You’re clutching the sheets around yourself, laying on your side, hands tucked under your chin, almost childlike. My hands thumb the pages of my book back and forth, back and forth. In the single second I look at you, I take note of your brown eyes, thick brows, and tan skin.

“Oh, don’t worry about it,” I say, eyes shifty, unable to maintain contact even in regular conversation with people I know.

You rub your face, and it’s then I see the gauze wrapped around your wrist. I avert my eyes and step to walk away, but you roll onto your back and ask, “What time is it?”

I’d check my phone and tell you exactly, but it’s sitting somewhere else in a manilla envelope, along with my wallet—probably in a drawer in some closet, filled with other peoples’ phones and wallets. That is, if they even had them when they came in.

“Uh, I think it’s close to like 10:30 or something.”

Thankfully at that precise moment, Chance comes in. So far, he’s one of my favorite scrubs. He’s kind and super-fucking-tall, not that that has any bearing on anything other than the shrunken feeling I get whenever he stands near me. It helps that I don’t find him particularly good-looking—I surely wouldn’t feel as comfortable around him as I do if I did. He looks over at me and says, “Mind if you give us a second? Gotta go over some stuff with ________.” I’m glad for the excuse to extricate myself from the situation. I say, “No problem,” and leave to find a place in the noisy common area where I can sit and read. Though I don’t want to be in the same room with a man I don’t know, I do quickly miss the haven of my—our—room. For the one day spent alone in that room, I felt safety—comfort—in the solitude of being new, a stranger, in this isolated world. I’d sat in our bright room almost all day yesterday where the sounds of the other people didn’t bother me. I could just sit, surrounded by the comforting light and white walls and just be. It was both a subtle and stark contrast from the bedroom I’d confined myself to before my admittance here. There was no roommate in the before-room. No blood pressure monitors. There were many shelves of books to choose from, not just two. But even with headphones there was an endless drone in the before-room. The constant noise of Fox News but also of history and discomfort—of forcibly being back in a house I’d left for the safety of college. Funny how an invisible thing can send someone back to the start—can send the world into a panic. The before-room had green walls and one window, blinds and curtains always closed. It, too, had voices but those weren’t strange to me. They were engrained in my mind—in the walls. Any effort to finish a semester of college in the before-room was always going to be a losing battle. But, for now, there’s no college, there’s no drone, there’s no noise, and there’s no before. There’s just now, and that now has been invaded by a unknown entity, expelling both the solitude and me out of our room. And right now, instead of our room, I see the purplish-red mess of hair that I know belongs to Oz, as he sits at one of the tables, drawing with the washable, nontoxic markers the staff keeps stocked for us.

At the moment, it seems like half of the little more than a dozen of us patients have chosen to stay in our rooms and watch TV, asking for help when the channel needed to be changed. The other half are either stationed at various tables or in one-on-one sessions with therapists or psychiatrists. Oz and I are the only teenagers out of everyone. I’m 19, and he’s not far behind. As far as I can tell, the majority of the other patients are nice, some even welcoming. There’s even a kind of camaraderie between some of the patients. In the common area, we patients have three scintillating options for how to spend our free time: play cards, color, sit.

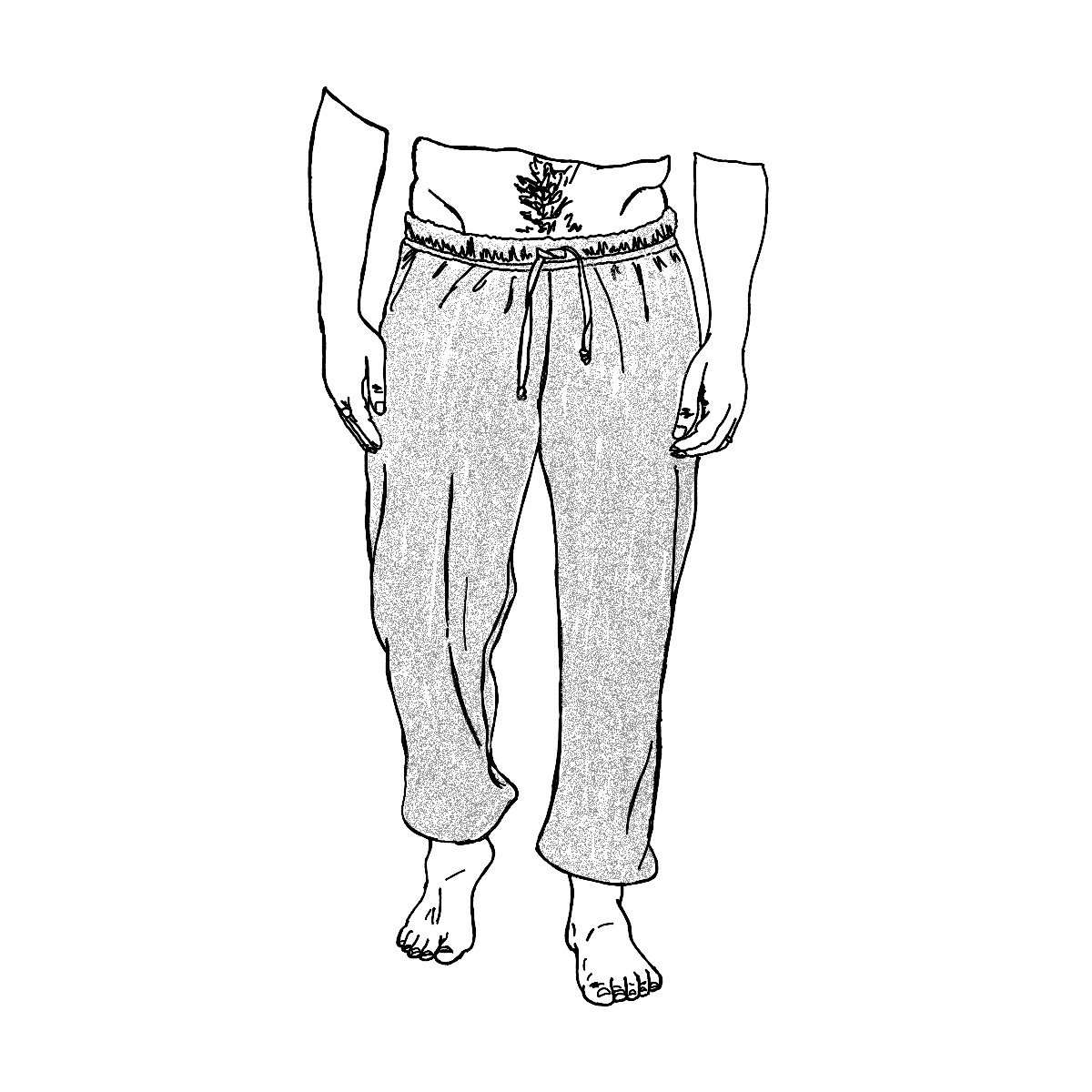

I plop myself down at the same table as Oz and we exchange heys. He keeps drawing, and I try my best to dive back into Rooney’s words. It’s not very long before you sit next to me in one of the huge, blue, too-heavy-to-pick-up-but-easy-to-slide chairs. You’re still in a hospital gown, which piques my interest as to what exactly you were wearing when you were admitted … if anything.

“So, how long have you been here?,” you ask me, hands clutched in front of you on the table. I hesitantly look up from the pages of my book, which was already difficult to focus on given the near-constant beeps and boops, nurses running back and forth, and TVs from other patients’ rooms. I notice Oz bring his arms closer to his body and dipping his head closer to the paper he’s coloring.

“Um, I got here early yesterday morning. Self-admitted.”

“Gotcha, gotcha.” You’re clearly still groggy. It’s now that I notice you chewing gum, even though I haven’t seen a hint of gum’s existence here. “Man, I was out of my head last night. I don’t really know what happened. I didn’t have any clothes on when they found me.”

“Oh … damn,” I say, because what the hell else was I going to say? Oz’s eyes go a little wider. His eyebrows arch. You don’t notice.

“Yeah. I need to call my brother. See if him and his husband can bring me some clothes.”

Oh … damn. Surprise registers on my face. “Mm yeah. Parents aren’t the biggest fans of having two gay sons, but they’re cooler about it now than they were.”

What an interesting development. In my 19 years of life, I’d never met an openly gay person who was significantly older than me, and I’d never been comfortable around anyone who was openly gay—because I couldn’t, or wouldn’t, let myself follow suit.

“What about you? Are you—?” You’re cut off by the announcement of snack time, and I’ve never been happier to eat a bag of baked low-fat potato chips. But I’m still on guard now—and, at the same time, I want to tell you everything. Maybe you can tell. I’m sure you can tell. It doesn’t help that in the light of the common room I can see your face better, with its defined jawline covered in that stubble my eyes keep coming back to. Even with the hospital gown, I realize a very unfortunate truth: You’re kinda hot.

***

By the afternoon of the next day, the unthinkable happens: I let myself sit in bed and read after our group session with you in the room. Yesterday, after getting some food and, more importantly coffee, in your system, your personality started to show. You weren’t skittish at all around the other patients, nor they around you because of your charming pseudo-retired surfer dude vibe. By proxy, I let myself be a bit more talkative, too, especially with Oz, whose guard slowly let down—but not all the way. This morning, you even made a few of the orderlies chuckle by hustling other patients, myself included, for their coffee and sugar packets. At every group meeting and meal since your arrival, you, Oz, and I have sat together. My desire for solitude has been discharged, and I allow myself to feel contentment with companionship.

My ears perk up as the steady slapping of water against the bathroom tile stops, replaced by barely audible drips. I try to force my mind into the narrative on the pages before me, but my brain keeps pivoting to the notion of there being a naked man in close proximity to me. Earlier today your brother dropped off clothes for you, and I do my best to keep my eyes glued to my book as you pad over to the cubby where the paper bag sits. I notice the towel wrapped round your waist as you pick out your outfit. I’m doing my best to pretend you’re not there when you say, “Hey, Ethan.”

My eyes are still glued to the book when you say, “How does this look?” It’s not the clothes you’re asking me about. When I look up, my eyes land directly on your exposed dick. “Well, what do you think?” The thin white towel is on the floor in a semi-circle.

What I think is this is the first time I’ve seen a dick that wasn’t encased in my phone screen. This one is being presented squarely, directly to me, for my eyes only. So, what else could I say? “It’s okay.”

Your jaw drops and you laugh, incredulous. “Just okay? Damn, Ethan, you really know how to humble a guy.”

I feel my face turn redder than it surely already was. “Well, I mean. It’s not bad.” And it wasn’t. Not in the slightest. But how am I supposed to tell that to the middle-aged man in the psych ward who just flashed me and sussed out the fact that I was also pretty acutely gay?

You stand in front of the mirror and say, “I think it’s pretty nice.” And I agree. I agree because a man just showed an interest in me, the kind of interest I’ve been craving for years. You say it’s my turn. My blood boils underneath my skin. It ripples through my body and begs for air. For release. I hate my body and yet I expose it to you. Just because you’re gay and you said so. But maybe that’s not the whole truth. Desire contains multitudes after all.

“Not bad,” you say and start to put your clothes on. “I knew you were gay.” It’s my turn to scoff, to act like I don’t hate the fact that I must’ve been so obviously queer to you. But I think I hate that your clothes are back on even more.

***

A couple nights later, after you’ve shown your dick to me multiple times and told me about each time you jerked off in the shower or on the toilet, after you’ve told me about your life, the years you spent in California and how much you love David Sedaris, we lay there in silence a moment. It’s been at least 20 minutes since I was given my nightly meds. We are separate entities, mirroring each other in our beds. The door is all the way open, the fluorescent lights an invasive presence. After another infinite moment you get up, dressed in the gray sweats and white tee your brother and his husband brought you and gently push the door, almost close it. Now only a small sliver of those fluorescents seep in, wishing they were embodied so they could push back against the door.

The white tee is the first to come off. You toss it on your bed as you quietly step, step, step closer to my side of the room, my heartbeat quickening with each bare footfall. You’re right next to me. Your face is inches, centimeters away from mine. The mattress depresses underneath your right palm as you plant it beside my head. Then your lips are on mine, your tongue slips in between, carrying the minty, chemical taste of your ever-present nicotine gum. You put the rest of your weight on top of me. We’re pressed against each other. The only layers between our skin are my clothes, the thin white sheet, and those gray sweats. They don’t stay between us a second longer. The anxiety of being discovered fuels the urgency. In seconds the sweats are around your ankles, your lips are on my neck and your okay dick is grinding repeatedly against my pelvis. It’s the best thing I’ve ever felt. Another man’s skin against mine. An intimate contact that’s only been alien, confined to my imagination. A physical desire that’s never been reciprocated, let alone attempted—let alone discussed.

It’s the most terrifying thing I’ve ever felt. Between each thrust against my hip my mind is taken to that sliver of fluorescent light, waiting for it to expand, for some shadow to push that wooden door open and put an end to this ecstasy and gratify my fears. But there’s something lurking below the pleasure, below the fear. It’s emotionless. Analytical. It notices how animalistic, primal even, each thrust into my skin is. How each time you whisper oh, baby it’s just part of the routine, a script. My mind records every moment. How your moans intensify. How when you’re about to cum, you announce it and proceed to do so on my torso.

I wonder: what’s going through your head? How does it feel to be humping a closeted nineteen-year-old boy, twenty years younger than you, in the bedroom you share in a psych ward? Are there any emotions there? Guilt? Shame? Lust? Or is my body just another tool, an implement you’re using to get off?

But these are thoughts for another time—another me. You immediately rush away and as quietly as you can roll into your bed because some higher power let us hear the footsteps before the beam of light becomes a flood and the shadow I feared materializes. It stands there, takes a few steps in, but never strays from the box of light on the floor. It doesn’t shut the door on its way out.

I can feel my heartbeat in my fingertips, in my toes—and, well, something else that’s become increasingly hard to ignore.

You get up and walk to the bathroom, gently pushing the door to—not quite shutting it— again, as you do. I hear you pee, quickly followed by the super-powered flush, and then a towel is tossed on top of me, so I’m able to wipe you off my chest. I put the towel under my bed, and from your side of the room I hear you ask, “Are you still hard?” The truth is what it is.

“Um, yeah, yep. Definitely still hard.”

“Well … you gonna take care of that, or do you wanna come over here?”

My first thought is to just force myself to let the trazodone do its job and go to sleep. Better than risking getting caught again. Better than adding anything else I might regret later. My second thought: I did not just get dry humped for what was admittedly probably no more than thirty seconds (surprising considering your age) only to lie in bed having been used like a teenager’s sock.

So, I take a few butt-ass naked steps over to your bed and let you cradle me in the nook of your left arm. My boldness doesn’t last. I’m immediately terrified of being discovered. Of the shadow reappearing, silhouetted in piercing, pale light. The longer I take, the more anxious I get. When the climax does finally come, there’s no satisfaction there. No catharsis. No time to lie in this other man’s arms and relish in the ecstasy of skin touching skin. As I get up and retrieve the towel from under my bed, you admonish me for taking so long, only barely joking. I put my clothes back on, and you ask me to give you the towel. I don’t really think to question why before you’ve folded it and stuffed it in your pillowcase.

Perhaps there’s someone out there who would find this idea hot. I am not that person. At the moment though, I’m too tired to be grossed out. As soon as my head hits the pillow, I start to feel the trazodone. How it increases the weight of my eyelids ten-fold. How it erases any shame I might feel if I were to stay awake in this dark, dimly orange room, listening to the first man to intimately touch me snore.

***

A Fleetwood Mac song is playing as the three of us stand in a line against the barred balcony. The sun’s rays are columns on our faces. Other patients are in this cage with us, feeling the sunlight and the wind. The music is coming from the orderly’s phone behind us. We get to do this every other day, come out and request songs to listen to. Today, I managed to convince you to stop watching Atomic Blonde on the TV in our room and join Oz and I. With my fingers tapping the rhythm against the bars, I make a note to myself to write this song down on the sheet of paper I’m compiling a playlist on. So far, I’ve made three while here: one for an orderly, one for another patient who was discharged yesterday, and this one for Oz.

The song ends and, as we’re ushered back into our white-walled enclosure, one of the psychiatrists approaches us, and tells you it’s time for your meeting. You go with him, while Oz and I find ourselves a table in the common room, specifically the one closest to the markers. Oz doodles what is supposed to be me as an anthropomorphic fox as I scan through the playlist, trying to think if I’ve left out any of my favorite songs.

Sitting there, we talk about school and how Oz wants to go back to college. We talk about our conservative families and how hard it’s going to be to have to be with them again. We talk about Adventure Time and music and everything else there is to chat about with your psych ward friends. I eventually trade my playlist for an intricate coloring sheet of a flower and our conversation lulls.

“Hey … um,” Oz starts. I look over at him. Behind glasses, his eyes are glued to the paper in front of him. He keeps drawing, coloring over the same spot. “Are you okay with ________? Like he hasn’t tried to do anything to you, has he?”

In an instant, my body is a mess of nerves. His question shocks me, not only because I’m now terrified everyone here knows about everything you and I have done together here, but also because I’d come to see you, me and Oz as a kind of trio. We always sat together at group sessions and meals, and we’ve been able to laugh together in this place, too. Underneath that scared, defensive feeling is the worry that Oz may have been uncomfortable around you this whole time and I didn’t notice.

“I just. I don’t know,” Oz continues. “Some of the things he says to you just kinda make me uncomfortable, and I just wanted to check with you to make sure you’re okay and that he’s not doing anything that makes you feel uncomfortable.”

It’s true. Each day you’ve gotten more brazen. The way you look at me. The amount of innuendo you direct to me. The stray times you touch my leg under the table. Everything you do that sends a flutter down my spine is scary but also so wanted. Each time makes me wish I was with you anywhere that would allow me to hang onto you, safely. My response to Oz is almost immediate:

“Oh my gosh, no, no.” I force a laugh. “I know he’s kind of a lot sometimes, but really, he’s harmless.”

Oz looks up from his doodles and into my eyes.

“I really appreciate you checking in with me, though. Seriously”

His eyes fall. “Yeah, of course.”

The two of us sit there in silence. A few minutes later you sit at the table, and Oz is taken to his therapy session. He goes wordlessly.

“Is Oz okay? She seemed down,” you ask. It makes me happy that you sound like you genuinely care. And yet.

“He,” I say. “And yeah. We were just talking about family stuff.”

After realizing your mistake, you apologize, and ask if I want to watch TV, but I decline. “I think I’m gonna read.” Maybe I shouldn’t want you the way I do. Maybe it’s not you I want at all but the feelings you unlock, those closeted, malnourished, and ultimately neglected feelings. Maybe I should be made uncomfortable by you. I guess, in a way I am. There is discomfort, and it’s fueled by insecurity, by self-hate, and, of course, by the fact that a psych ward isn’t intended to be a place for two guys to make out. And yet, it’s the only place I’ve ever been able to act on, to validate, that feeling of longing that’s been more-or-less ever-present in my life. So maybe I should take advantage of the opportunity.

***

It’s my ninth day in this hospital. It’s my last day in this hospital.

It’s your and Oz’s last day, as well.

After our final breakfast together, while we wait for our clothes to come back from the laundry room, I kiss you, hard. This is the last chance I get, so I decide why not get cinematic with it? I lift my leg up to your waist, and you catch on immediately, grabbing it and the other leg as I raise it. Your strong arms hold my thighs as your nicotine-flavored saliva enters my mouth for the last time. I wish I could say this urge I felt to never leave this moment was motivated by anything romantic, pure, or good; that’s just not the case. What locks my lips to yours is desperation. What keeps my arms wrapped around you after you can’t hold my weight anymore is fear. The fear that this decently attractive middle-aged man I met in the psych ward will be the only man who will ever desire me. The only man to touch me in the way I’ve always wanted. Worse, the fear that I’ll only ever feel wanted—and safe to be such—behind closed doors.

I don’t want to want you. I really don’t even want you to want me. I want to be wanted by a man I haven’t met yet, one who doesn’t make me feel used, one who makes me feel safe, one who isn’t two decades older than me. The one I haven’t met yet. And maybe won’t for years to come.

We hear someone walking in and separate. It’s Chance. He tells me it’s time for my last one-on-one therapy session. He looks at you and says, “Your ride should be here any minute, so make sure you’ve got all your stuff. Someone will come by with discharge paperwork soon.”

“Awesome. Thanks,” you say. That California accent coming through. Chance leaves, and when he’s out the door you wrap me in one last hug. It feels real.

I wish it didn’t.

This is the last moment we share together in Room 448B.

***

When I come back to the room after meeting with my assigned therapist, who has me recount my post-discharge game plan (get away from my parents’ house as soon as possible and stay at my friend’s house in Oklahoma). It is just as it was before you were there. The sun lights the pale, blue walls and the white tile floor. I make sure all of the clothes I brought with me are in the original brown paper bag I was given to put my dirty clothes in. Oz has already been discharged, too. I gave him the playlist and my Twitter username. He gave me the drawings he made of me and one of himself. They’re very queer, and I love them. I grab my two books off the shelf but pause when I notice Calypso has something wedged in it. Out falls a washable, purple Crayola marker. On the inside of the back cover, is your cell phone number and mailing address. Mail here when you’re done reading, reads the purple scrawl.

Part of me wants to kill you for using a purple fucking marker on my book. The other part—the one that prevails—just smiles. You’ll never see this book again. At least, not this copy of it. I put the books in the paper bag, and a couple hours later, Chance tells me my parents are here. My heart drops. I check the paper bag once again just to make sure I have everything.

I don’t. In fact, in the bag there’s something that didn’t arrive here with me: a pair of men’s black athletic underwear. Missing: a pair of my own American Eagle underwear.

I scoff into this brown paper bag, my heartache about going home momentarily forgotten. You stole my underwear. You gave me a pair of yours. Is underwear trading a gay guy thing my closeted ass just didn’t know about? I place everything back in the bag and decide this is the only piece of our story I’ll tell. It’s too funny not to, and it’s the only piece of truth that feels safe, acceptable to share.

I don’t want to want you.

But that doesn’t stop me from texting you when I get home.

Illustrations by Jo Davis-McElligatt

about the author

Ethan is a white man with a beard and brown hair. He is smiling and standing in front of a tree with a red brick building in the background, and wearing a plaid flannel of white, navy blue and light red over a red tee.

Ethan Wood is a recent graduate from University of North Texas with a BA in English/Creative Writing. His writing has also appeared in Volume 22 of North Texas Review and NTR Online. His personal essay Lapse was nominated for the 2022 Norton’s Writer’s Prize. He currently lives in Denton, Texas with his cat, Ollie. You can find him on Instagram @ethantw00.